“Really pleased to have teamed up with Gareth Cobb from The Fold Studios who has written a thought provoking and informative guest blog for the EDT website where he shares his tips and advice for drummers who are new to the world of the recording studio”:

As an engineer and producer with 10 years of experience working in a studio environment with drummers of all abilities, ranging from top session drummers to absolute beginners coming in with their first bands, Pete has asked me to share some of my top tips for drummers coming into a recording session.

Please be aware that there are many sweeping generalisations represented in the following paragraphs. The point, for example, about minimising your playing may not be fully relevant for those of you playing in a prog-metal-fusion-deathbop drum trio.

Think of this as a general guide that will set you in good stead for 99% of studio sessions you’re likely to be involved in. It is written mainly from the point of view of those drummers who are coming into a session with a band or solo artist, without much studio experience and not really knowing what to expect. Distilled within the six main points made here are the vexatious cursed mutterings of much wasted studio time, the ghosts of mistakes made, the wounds of regrets keenly felt all spat out the other end into this blog, that you may avoid some of the more menacing pitfalls of studio recording…

1. Rehearse, refine, rehearse, refine.

Given that going into a professional studio generally costs money, it is important to make every second in there count towards creating a finished product you can be happy with. So unless you have the luxury of being able to afford weeks on end in the studio, this means putting as much time into pre-production as possible. Record your rehearsals with a digital Dictaphone or basic recording setup and listen back critically. Pay particular attention to how the rhythmic elements of all the instruments work together. Listen to how the kick drum patterns work with the bass guitar. These are all elements that you and/or your producer will certainly pick up on in the studio, so it makes sense to try to iron out as many of these issues as possible before you even set foot in that environment, rather than spending that precious studio time correcting simple but vital rhythm track elements.

The idea is to strip away all of these variables and doubts from your mind so all that’s left to do when you walk in the studio is to execute to the best of your ability.

You will always hear things you may want to change, adapt and evolve when you are in the studio – it’s part of the fun of a dynamic studio experience – but these should be the minute details, worked through meticulously for the purposes of making the absolute best of the material.

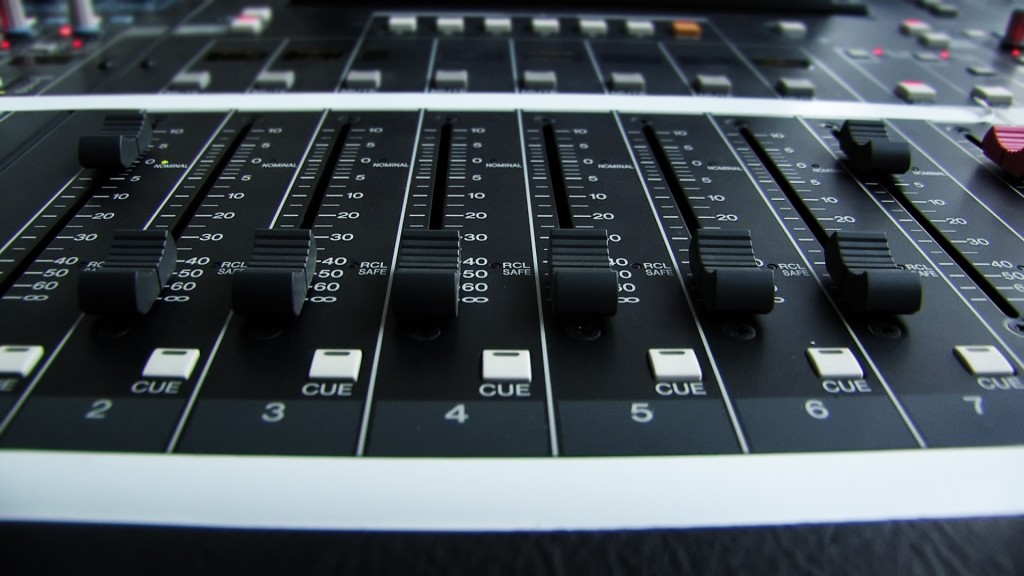

2. Be in control of your own faders.

It’s an incontrovertible fact. Your whole rhythm track will sound better if you are balancing the levels correctly and appropriately in the room as you play. Imagine that there is only one microphone for the whole drum kit. Try to play in a way that will sound naturally well balanced on that one mic. If you are playing a “middle of the road” rock song and you are hammering the hi hats twice as hard as the snare drum, the whole rhythm track will sound weak, thin and harsh.

Of course, more often than not the engineer will have several close mics and will have the ability to balance the kit through level mixing, but you can always hear when the engineer has had to force the results.

Famously the drums for “When The Levee Breaks” by Led Zeppelin were recorded by just a stereo pair of room mics, way above the kit. This is one of the most famous drum sounds in rock, and would simply not be possible without John Bonham’s ability to perfectly balance the kit through his playing.

3. Tuning.

Another case of getting it right at source. Tuning drums can seem a bit of a mysterious dark art and everyone has something different to say about it. I’m not going to go into specific details about tuning as I feel there’s a wealth of information on the web which covers that (see this video by DW’s John Good for a good starting point). What I will say is, keep it a high priority in your mind. Research as much about it as you can on the internet, ask your drum tutor’s advice, and try to slowly develop your preferred methodology. The longer you experiment, the closer you will get to achieving your goal of being able to consistently attain the sound you want, and this is something you should take with you into every studio session. There is no way on earth that any amount of tinkering with EQ and compression on the recorded material can compete with drums that have been well tuned in the first place.

Also try to make sure that your drum heads are in good condition. I have never been a subscriber to the idea that heads should always be brand new when going into the studio, but different ages of drum heads do produce dramatically different sounds, which are appropriate to different styles. You can easily get away with quite old skins if playing some rootsy folk, blues or country, but if you’re after a really responsive snare sound with a mighty crack for some ultra-modern sounding rock, you should be looking at new or just played in skins.

4. Lose the showmanship, keep it appropriate.

It’s a fact that all instrumentalists should do well to remember; the vast majority of listeners to the vast majority of music want to listen to the lyrics and main melody. That is not to say that the rest of the instrumentation is unimportant, but if you are always thinking of how well the vocals are delivered through the instrumentation, you’re on the right track.

This ties in with point number 1 as you can use the pre-production time you put in to listen back objectively to your demo recordings and figure out exactly how much you need to play. Try to look at it from outside of a drummer’s perspective. Talk to the rest of your band and see what they think, and don’t be afraid to share your opinions of their parts, and how they work with yours. Remember, this should not be an ego issue, rather a collaborative effort to make the final recorded material as good as it can possibly be. If that means playing three and a half minutes of straight repetitive groove with no fills and no crashes then embrace the challenge. Showing your character as a drummer by virtue of your groove rather than your chops and fills is one of the most advanced tests you can hope to go through, but also one of the most rewarding. Have listen to “Lose Yourself To Dance” by Daft Punk and ask yourself “Would I have been that restrained if I was recording drums for this track?” The answer is probably no – it would be for most people so there’s no shame in that, yet the drums on this track were played by J.R. Robinson, one of the most decorated and respected session drummers in history.

5. To click or not to click

Here is an example of one of the most frequent conversations I have as a producer and engineer:

Me: “OK so do you know whether you want to use a click for these recordings?”

Band: “Yes we definitely want to use a click”

Me: “OK great. Do you mind me asking why you feel you should be using one?”

Band: “Errrm… well just cos… I mean… You know… because umm…”

Herein lies the problem for me; the assumption that you should use a click in all studio situations without a second thought. Now let’s be clear, I have nothing against click tracks. I use them most of the time but I do think you should have a reason to want to use one, and these reasons should outweigh any potential disadvantages, such as potential loss of performance energy or lack of experience with a click.

If you do decide to use a click, and you aren’t very experienced as a drummer at recording to one, try to throw this into your practice routine as much as possible before your session. If you have the means, try recording yourself to a click with a basic setup and assessing the results, aiming for incremental improvements every time. Playing to a click track is a highly disciplined skill in its own right and being thrown into a studio session using one without any experience can blow a whole day of studio time. At best that’s going to put you critically behind schedule and at worst you can come out with nothing useable!

6. Two different worlds

The live environment and the studio. Try not to get bogged down with the idea that if you do something in the studio that you cannot replicate live, this somehow means that the results do not properly represent you. On the contrary, studio recordings should represent the highest aspirations of your sound as a band or artist. In the same way that movies scenes are shot multiple times, from different angles with green screens and CGI effects, putting together a quality studio recording is also an illusory process. The final results should sound like a cohesive band recording, but there may be many tricks and uses of artistic license along the way. You should not feel restricted in the studio to only play what you play live. What’s more, you should be open to suggestions from your producer/engineer and/or band mates as to how to make improvements. Try not to dismiss suggestions on the basis that “I’ve always played it this way” or “but I wouldn’t be able to do that live”.

A classic example here would be use of the rimshot. In my experience, many drummers rimshot pretty much all the time and identify it as part of their sound. That’s absolutely fine in the live environment and also works well on a great deal of studio recordings. But there are also many times when the snare should be providing a solid backbeat with a deep, fat sound and not jumping out of the mix right up in your face. In these situations rimshot hits lose some of the fatness and sound too punchy through the mix. The producer will be looking for the right snare sound for the track without prejudice and may suggest not rimshotting and/or tuning the snare low which may be counter to your natural instincts as a drummer. However it is usually a good idea to go with his or her suggestions as it is their job to be looking a few moves ahead, and also at the bigger picture (If I will allow myself to finish on a mixed metaphor!).